After years of increasing tension between General Aviation pilots and organisations on one hand, and airfields and airports seeking increased controlled airspace on the other, the signs are that disagreements over new airspace proposals, and even the continuation of some existing controlled airspace, may be headed to court. This simmering discontent is being bought to a head by one airport’s refusal to amend its controlled airspace, leading to the revelation that once it has granted new controlled airspace to an airport, the CAA cannot withdraw it without the consent of that airport.

For many years, controlled airspace was low on the list of problem areas when the health of the GA industry was being discussed – issues such as rising costs, bureaucratic regulations and the closure of airfields were far more immediate threats. Nevertheless, as the amount of controlled airspace over the UK steadily increased, concerns began to be raised over issues such as Visual Flight Rules (VFR) and non-radio or non-transponder traffic being forced to take long and sometimes less-safe routes to avoid controlled airspace. Access to airspace became a hot topic of conversation amongst pilots, and airprox reports and actual mid-air collisions have highlighted the increasing dangers of ‘choke points’, where aircraft are funnelled into increasing narrow gaps between areas of controlled airspace.

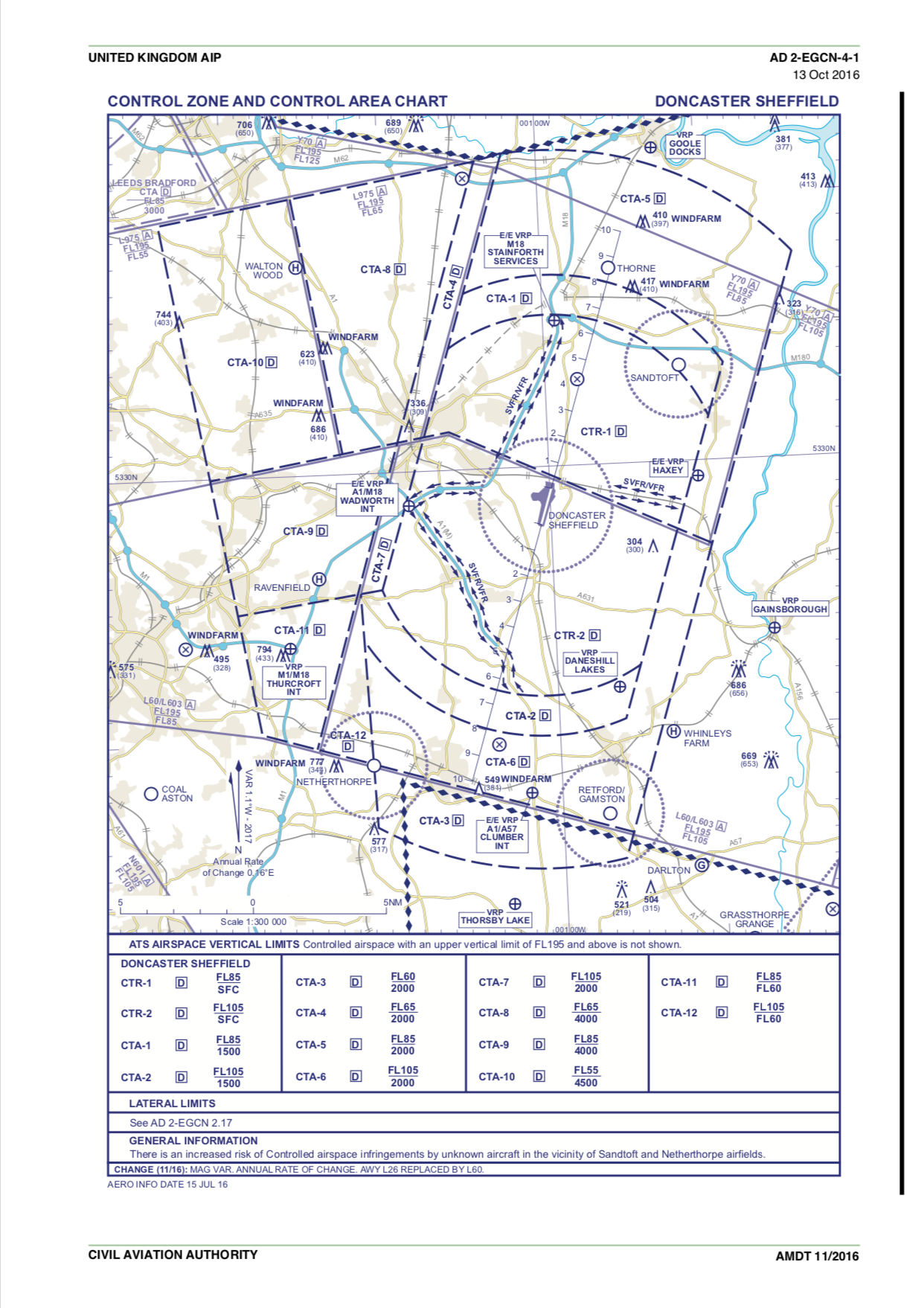

However, probably the ‘tipping’ point into open hostility towards new airspace proposals has come as an increasing number of relatively underused airports and airfields have applied for controlled airspace based not on existing traffic, but rather projections of how they expect their traffic to increase. This has led to airfields such as Doncaster (Robin Hood) and Norwich being granted and retaining large areas of controlled airspace, even though their Commercial Air Transport (CAT) movements have often failed to match their forecasts of strong growth. There is also disquiet over the amount and complexity of the airspace granted to airports – apparently even relatively quiet airports such as Southend or Norwich seem to require more Class D airspace than, say, London Gatwick, which handles many times more CAT movements.

As new controlled airspace has become more controversial, so more attention has been focussed on the process by which the CAA grants. Known to insiders as the ‘CAP725’ process (after the CAA publication which detailed the procedure), until recently the method of applying for new controlled airspace had remained largely unchanged since the 1990s. In essence a ‘sponsor’ (usually an airport) would be responsible for coming up with a design for the airspace it wanted, and was also responsible for running a consultation with interested parties such as the GA community, and then reporting the results to the CAA. However, for reasons that are not clear, much of the ‘CAP 725’ process takes place behind closed doors and much of the associated documentation is withheld from those who would be affected by the new airspace. Suspicions have grown that some of the organisations applying for controlled airspace are being less than totally honest with the CAA about the merits of their case and the results of their consultation.

In the face of increasing pressure the CAA commissioned an independent review of its ‘Airspace Change Process’ (ACP) and the result were published in December 2015. Amongst other findings, the review found that:

- There is a lack of transparency in the process, [which] has created suspicion amongst some stakeholders who are not confident that their interests are well represented. The report’s authors described this as their “…single most important observation, as the lack of visibility hinders trust and effective relationships.”

- The consultation process is viewed with great suspicion by some consultees who perceive the change sponsor as ‘judge and jury’ in dealing with the consultation responses. Not surprisingly, report noted that: “There is a potential conflict of interest here…”

- Unlike other planning processes, there is no appeal mechanism available aside from a Judicial Review.

The review made a number of recommendations for a new ACP procedure, including:

- Greater transparency and a principle applied that all documents should be public except where sensitive information must be redacted. Indeed: “…it is particularly important that information used to justify an AC[Airspace Change] decision is made public if at all possible.”

- The creation of an ACP Oversight Committee for major changes, introducing additional people both from the CAA and external stakeholders.

- A much more tightly controlled consultation process with the CAA gathering consultation responses.

- The introduction of an appeals mechanism.

As a result of the review, the CAA have now published a new ACP procedure, effective from the beginning of 2018, in a CAA document ‘CAP 1616’. This new procedure deals with some of the deficiencies of the old ‘CAP 725’ methods, and includes requirements for much greater transparency and access to documents. However, just as hope has been raised for a fairer airspace change process, new developments have come to light which threaten to place airspace decisions in the hands of the courts, rather than the regulator.

Although just about all General Aviation organisations have had something to say about the amount of new controlled airspace being approved by the CAA, the British Gliding Association (BGA) has generally been most active and vocal in challenging new airspace proposals. Indeed, it has become something of a tradition that at the BGA’s annual conference, usually held in late February, its own airspace ‘guru’ – John Williams – will brief delegates on the latest developments in airspace. The 2018 BGA conference was no exception, and the hall was packed with standing room only as John listed just some of the airspace proposals currently before the CAA. He singled certain proposals for particular criticism saying that in some cases it seemed the consultants were “blatantly uninterested” in overall airspace safety. He also said that although the new ‘CAP1616’ process addresses some of the problems highlighted in the independent review, what is really required is a change from an adversarial process to a collaborative one. He singled out the need for an evidence-based approach to achieve proportional proposals rather than ‘commercial grabs‘ and said that the regulator (ie the CAA) must be prepared to say no to those who do not consider the needs of other airspace users.

John was followed by Dave Curtis of National Air Traffic Services who agreed that collaboration is the way to go and held up the cooperation between the gliding operation at Dunstable and nearby Luton airport as a ‘brilliant’ example of flexible airspace. He also won friends in the hall by saying that whilst NATS needs to protect Commercial Air Transport, they also need to look after other airspace users. Speaking about the need to modernise airspace, he offered the technical but important detail that airspace design should use a new model that assumes a 6% climb gradient rather than 4% – in other words better representing modern jet airliner performance rather than 1950’s propeller aircraft, and thus reducing the amount of controlled airspace needed.

It would take a brave person to present a counter view in front of an unashamedly partisan audience, but just such a person was Jon Round, sent by the CAA to present the regulator’s point of view. Whilst saying that he heard the audience’s frustrations, he insisted that airline passengers were contracting for ‘zero risk’ when they bought a ticket, and the needs of GA were a secondary to that consideration. On a more positive note he went on to say that the CAA want greater integration, more class E airspace and more flexible use of airspace. However, he revealed a hitherto unknown factor in the airspace equation. He recalled that in 2016 the CAA had promised that year’s BGA conference that Doncaster’s airspace would be ‘rolled back’ following a Post Implementation Review (PIR) that is part of the airspace change procedure. In the Doncaster PIR, published almost 10 years after controlled airspace was established, the CAA suggested reclassifying 10 of the 12 separate control areas (CTAs) that surround Doncaster’s Control Zone (CTR) as Class E (less restrictive than the existing Class D), and raising the base levels. However, he revealed, Doncaster ‘refused to play ball’ and the CAA had discovered that it lacked the legal powers to enforce the airspace ‘roll back’ it had promised. In other words, the CAA can create new controlled airspace, but cannot remove or amend it if the sponsoring airport refuses to cooperate.

The CAA’s revelation brings back into focus the most fundamental question of controlled airspace around an airport, as first reported by FTN last year. Are CTRs and CTAs a national asset, allocated according to the needs of all airspace users or, as now appears to be the case, once allocated by the CAA do they become the private property of the airport, to do with as they see fit?

As the GA world awaits the CAA’s decision on various new controlled airspace proposals, and in particular Farnborough’s controversial plans, the powerful GA All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) has formed an airspace group which has just published its programme. It notes that: “The development of UK airspace has resulted in a number of minor regional airports with limited or no public transport services owning areas of inefficiently utilised controlled airspace many times larger than that required by Gatwick airport, which is one of the UK’s busiest international airports. This is a major threat to GA as it reduces the uncontrolled airspace available to GA and dangerously funnels aircraft together within it into what are known as ‘choke points’ or pushes them close to hills or over the sea. There are currently a number of proposed airspace changes that, if approved, will result in dangerous choke points, for example around Farnborough, Exeter and Oxford airfields.” The group also notes that large areas of the UK’s airspace are: “…unnecessarily ‘owned’ by airports and their shareholders and therefore unavailable for the wider public good. Allocating a scarce national resource to benefit one organisation to the cost of others that also need to generate income is anti-competitive.”

As the flying organisation leading the fightback against many of the current airspace proposals, the British Gliding Association are equally blunt. The BGA told FTN: “We are dismayed that it took so many years for the CAA to discover that they have no powers to change airspace. This further undermines the discredited CAP725 process, which is still running for a number of ACPs (including Exeter, Brize Norton and Oxford) that if approved will significantly increase risk outside the [controlled] airspace and permanently damage GA interests. It is extraordinary that despite having the opportunity to adopt a reasonable approach during a transition, the CAA insists on continuing in those cases with the entirely unchanged CAP725 process when they know it isn’t fit for purpose.”

It seems increasingly likely that the airspace battle will soon move to the courts. It is rumoured that a group of wealthy pilots are prepared to fund legal action should Farnborough be awarded the airspace it has applied for. Meantime, the BGA has set up an airspace ‘fighting fund’ (https://members.gliding.co.uk/ga-airspace-fighting-fund/). The BGA’s website says that: “Although much of the work is carried out by volunteers, inevitably there can be significant costs. Legal support isn’t cheap!” It also states that the fund will have a group of experienced and well respected trustees including Sir John Allison, Peter Harvey and John Williams.

Asked for comment on the revelation about its lack of power to remove or amend an airport’s airspace, the CAA gave us the following statement:

“The CAA has legal powers to make an airspace change decision in response to a request from a sponsor, such as an airport, following an established process. Once that decision has been made it can only be subsequently amended by making another decision, following the same process. So, although the CAA can approve the introduction of controlled airspace where it has been sought by a sponsor, it will require a fresh airspace change request following the same process to have that controlled airspace re-classified.

The objective of a Post Implement Review (PIR) is to test the impacts and benefits of the original decision once it has been implemented and in operation for some time, and assess if those impacts and benefits are as originally expected. If they are not, then modifications to the way in which the decision was implemented can be required to better implement the original decision. But these modifications cannot change the original decision.

A PIR may find the impacts of the airspace change are so different from what was expected that the change cannot be confirmed, however, this is only a possibility in some cases. Generally, the original decision cannot be reversed.”

It seems that legal battles over airspace are now almost inevitable, resulting in court cases that are unlikely to be either quick or cheap. Legal action carries risk for all parties (except the lawyers), but the GA community and its supporters appear to have decided that this risk is preferable to the potential commercial damage and safety risk caused to their industry by what they consider to be the vested interests of regional airports and their shareholders.