Is the content and delivery of the current EASA ATPL Theoretical Knowledge syllabus fit for purpose? It is a question asked by almost any student professional pilot commencing ‘ground school’ and faced with the daunting task of assimilating several thousand pages of knowledge across 14 subjects never before studied, and passing 14 written tests with a minimum 75% pass mark, all in as little as six months.

It is probably true to say that student pilots have never looked forward to getting stuck into the books with the same enthusiasm as they anticipate starting flying training. After-all, pilots mostly become pilots in order to fly aircraft, rather than to spend time in classroom lectures and self-studying from thick textbooks.

Nevertheless, for many years there has been a growing disquiet within the EASA aviation training industry, and the airlines that employ the products of that system, that the material that student pilots are required to learn as part of their professional pilot training is moving further and further away from the knowledge that pilots actually need for day-to-day airline operations.

This disquiet is being increasingly voiced in public and at the recent Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) International Flight Crew Training Conference, a string of speakers and delegates lined-up to criticise current Theoretical Knowledge (TK) training and testing arrangements; with firm evidence now emerging to back-up their concerns.

The teaching and examination of theoretical knowledge for European professional pilots has altered radically in the past 20 years or so.

Before the advent of EASA and its predecessor the JAA, the most common route to a professional pilot licence was via the so-called ‘self-improver’ route, broadly similar to what is called ‘modular’ today. A pilot would first gain a Private Pilot Licence, then build flying hours and progress to a Commercial Pilot Licence in order to get some form of professional flying position.

After a further period as a First Officer – often up to 10 years – that pilot would then progress to an Airline Transport Pilot Licence (ATPL) in order to be eligible to captain an airliner. Each licence has its own associated Theoretical Knowledge course and exams.

Thus, the pilot increased their theoretical knowledge in stages, and with the benefit of actual (sometimes considerable) flying experience to bring to bear at each set of TK learning and exams.

With the advent of widespread self-sponsored ‘integrated’ courses for the ‘frozen’ ATPL, it was only necessary to pass one set of exams – those for the ATPL. Increasingly many flight schools have chosen to undertake the ‘ground school’ course, and associated exams, in their entirety at the very beginning of the ATPL course and before the student pilot has undertaken any flight training.

Thus it has become common for a student to be required to pass all 14 ATPL exams without ever once having actually flown an aircraft or even sat in a cockpit.

The reasons for delivering the TK portion of a professional pilot course in this way is debatable. Some flight schools say that success in the ATPL exams is a good indicator of how well a student will perform through the rest of the course.

Additionally, some flight schools offer a form of ‘money back’ guarantee for those who fail the course. Clearly the school will face a much smaller refund if a student is ‘washed out’ during ground school, rather than after they have commenced flying training.

Some instructors also believe that ground school is a strong test of the student’s motivation to actually be a pilot and the resilience they will need both in training and once ‘on the line’ working as a pilot. However, there is also often a sense amongst student pilots that the TK training and exams is a tiresome phase to be dispensed with as quickly as possible before ‘real’ pilot training can begin.

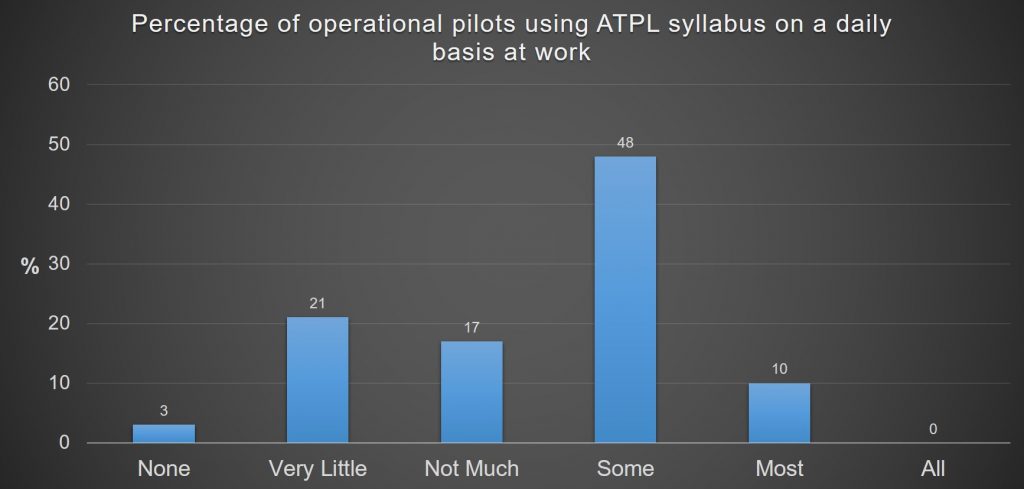

41% of pilots considered that they used either none, very little or not much of the ATPL syllabus on a daily basis ]

Although there has long been anecdotal evidence that many qualified pilots view the knowledge they acquired in their initial training as largely irrelevant, a new study by respected UK academic Dr Andy Taylor seems to provide strong evidence support to this viewpoint.

Dr Taylor is a University Teacher in Air Transport Management at Loughborough University and has been Course Leader for aviation programmes at three other UK universities. Before starting his academic career, Dr Taylor was cabin crew with Airtours International working up to base manager, before progressing to duty manager for airline handling agent Servisair.

In 2016 Dr Taylor surveyed over 100 current pilots about the applicability of the ATPL ‘ground school’ syllabus to their daily job as commercial pilots. The results of that study included the statistic that 41% of those pilots considered that they used either none, very little or not much of the ATPL syllabus on a daily basis.

Following up these results, Dr Taylor has now devised a study to test if the knowledge taught as part of the ATPL course is relevant to daily airline operations.

He created a short mock exam of typical ATPL questions, based on TK material from EASA flight schools and approved by the CEO of an Approved Training Organisation (ATO) currently delivering ATPL ground school. After validating the exam paper, it was tested on 94 of the respondents to the original survey.

The headline result of this new survey is that on average, those pilot achieved a mark of 44.5% in answering those questions. It was also interesting to note that on average, the more experience a pilot had, the lower the mark they achieved in the mock test. Although Dr Taylor is clear that the results of his research can only be considered as an indicator, and not scientific fact, it is difficult to avoid the message that at best, over half the knowledge taught in the ATPL TK ground school course is not used or refreshed in actual commercial operations.

The message of Dr Taylor’s research was independently collaborated both before and after he presented the results of his study at the RAeS conference.

In a panel discussion about how flight crew training could be modernised if it was possible to start with a ‘blank canvas’, one panellist – a current First Officer with a flag-carrier airline, described the TK ground school portion of their ATPL course as: “Boring, dull and pointless”. Another delegate, criticising the lack of printed hard copy training material made an impassioned plea: “Don’t just give me an iPad and say ‘That’s it’” A cadet pilot in the conference audience, probably too young to know how the training system worked before the widespread advent of self-sponsored integrated ATPL courses, wondered out loud if ATPL-level Theoretical Knowledge should be tackled once the pilot reaches Command stage, rather than right at the beginning of pilot training.

Speaking exclusively to FTN, Dr Andy Taylor explained that when he started teaching university students, those who were also learning to be pilots often raised the irrelevance of the ATPL Theoretical Knowledge that they were obliged to study. Many items that had appeared outdated when he had studied for the ATPL exams in 1996/97 (for example Loran C navigation) were still being examined in 2013.

The content of the ATPL ground school was also a common complaint on social media and in casual conversation. Dr Taylor told FTN: “In discussion with four ATOs it was assessed that there is around 1200 hours of learning in ATPL TK, which is equivalent to 120 academic credits, which equates a full year at university.

The ATPL knowledge was assessed as level 5 study, equivalent to the 2nd year of a university degree course. Many students told us that studying for the ATPL exams was the worst academic experience they had.

Gaining knowledge should be an engaging experience, more akin to how university students learn. Instead, ATPL candidates are being asked to acquire degree-level knowledge in subjects they have not studied before in just six – nine months.

There is also a difference between knowing something, and understanding it. In effect, we’re asking these students to remember ‘If you get this question, that’s the answer’. This is not new, but it is something that urgently needs addressing – we’re not training them to gain understanding, we’re just teaching them to remember a fact for the purpose of passing an exam.”

This professional opinion is supported by a trawl through some of the ‘question bank’ products which exist for ATPL exams. In effect, these question banks claim to replicate, or very closely match, actual ATPL exam questions. Infamously, one such question bank example is: “For what period of time does the ICAO president serve?”.

It is difficult to imagine any circumstances under which this information could be remotely useful in daily airline operations; nevertheless, many airlines base their selection criteria in part on pass marks achieving in the ATPL exams, not just the fact that the exams have been passed.

A typical requirement is for first time exam passes of at least 90%. In Dr Taylor’s view: “Pilots are being selected on the basis of an inferior examination system”.

If it is accepted that the existing ‘ground school’ and exam system is not fit for purpose, the question must remain – what to do instead? Some authorities have made changes to the format of their exams, for instance the UK CAA now require some alternative style answer choices – for example multi-select (ie select x choices from a list) and drop down (select dropdown words/phrases to complete a statement), and type in for numerical answers; rather than just straight multiple choice options.

Dr Taylor thinks a more radical overhaul is needed: “The authorities should strip back the ATPL TK requirements, which is a lot easier than changing the exam structure, this would be a good start. Then, when you’ve got to less syllabus, learning objectives and material to deal with, it is easier to make changes”.

One airline trainer told FTN that in their view, much of the theoretical knowledge that their pilots actually need is provided during the type rating and line training phases with the airline.

There is precedent for this approach. In the USA, the written exams for professional licences require, by common consent, a far less detailed knowledge of abstract information and in that respect the FAA exams can be said to be easier to pass.

However, unlike the EASA system, when taking a Skill Test under the American FAA system, the candidate will not even get to the aircraft before passing a thorough oral examination with the examiner.

This examination, which commonly lasts well over an hour, allows the examiner to assess the actual knowledge of the candidate across many subject areas and their ability to apply that knowledge in real-world situations.

The subject of ATPL TK teaching and examination is a sensitive topic and FTN spoke to a number of students, pilots, experienced trainers and recruiters who were unwilling to go ‘on the record’ with their comments.

However, unqualified support for the current course content and exam requirements was thin on the ground and indeed there was in some cases a cynical view that neither the authorities nor the airlines have any interest in improving the system and thus nothing is likely to change.

Some experienced trainer believe that when the Multi Pilot Licence (MPL) was introduced, a golden opportunity was missed to update Theoretical Knowledge as well as flying training requirements. FTN have been unable to find any sign that the authorities carry-out any effective or regular review of the relevance of the ATPL ground school course and exams; in the age of ‘Evidence Based Training (EBT), there is no indication that safety data from airline operations is being fed-back to those responsible for the current ATPL exam system.

Dr Taylor told FTN that he will continue to publicise the finding of his study, including giving a presentation at next month’s influential European Aviation Training Symposium in Berlin. It appears that much of the ATPL training industry hopes that the regulators will begin to take notice and maybe start to do more than marking their own homework.